Solve the Problem

As long as we have freedom of choice over what we eat, how much we exercise and a thousand other decisions, we should neither expect nor desire equality of behavior-driven health outcomes.

In a Michael Douglas film in 1994, Disclosure, he plays a male employee who is sexually harassed by his boss who tries to get rid of him by accusing him of sexual harassment to cover up a mistake she made. He gets continual emails from an unknown person who tells him that the answer is to “solve the problem,” in this case a production problem caused by his boss.

His problem at its base isn’t being wrongly accused of sexual harassment, it’s solving the production problem and being able to prove she is responsible. Far too much of the public health literature focuses on who has the problem instead of solving the problem.

There are 4,999,000 results for “health disparities” in Google Scholar. Here’s just one. In an article entitled, “Racial Disparities in Health Care With Timing to Amputation Following Diabetic Foot Ulcer,” the authors examine timing of lower-limb amputation across race/ethnicity and sex among older adults. They found that Black/African American “beneficiaries” are almost twice as likely to have a limb amputated as non-Hispanic whites within one year. Females were slightly higher than males. They were unable to find a reason but suggested that some early nonsurgical measures might be better choices than amputation. Of course, the underlying issue is diabetes, without which, they would not need to focus on amputations.

African American adults are 60 percent more likely than non-Hispanic white adults to have limbs amputated within a year but also twice as likely to die from diabetes. In addition, African American women are 50 percent more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic white women.

Excess weight can “greatly affect health in many ways, with type 2 diabetes being one of the most serious.” So rather than focus on amputations, or diabetes, the problem that needs to be solved is excess weight.

It may be in this case that African American (AA) women have different diets than other groups. For example, one paper in 2009 noted that self-reported portion sizes by AA women were large for most foods. It also reported that AA women had higher intakes of “total and saturated fat and sodium as well as “not avoiding fried foods.” Another study started a weight management program with 120 black women but, by the end of the 18th month, only 12 remained. These behaviors don’t sound like they are unique to any particular group, although excessive consumption of soft drinks may be, which involves massive amounts of sugar. If any of these factors are unique to this cohort, that would be important to solving the problem for this particular group, but not because it is a health disparity.

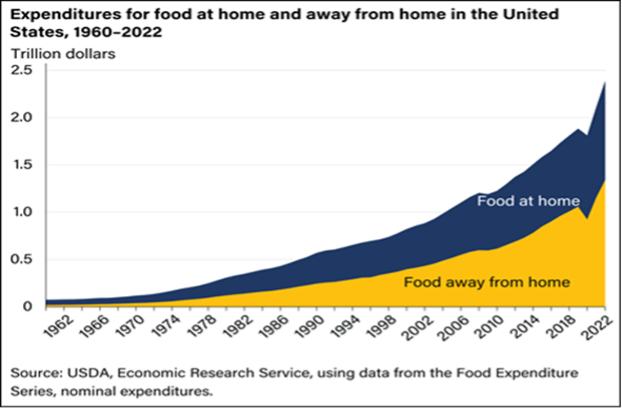

In fact, it is clear that obesity and diabetes cut across all socioeconomic groups in the U.S. Nearly half the country has diabetes or prediabetes and three out of four of us are overweight or obese. We also know that, for the country, excess weight gain started around 1980 which also coincided with eating more and eating out more.

The problem with eating out more is that restaurants typically have much larger portions, often two or three times the recommended serving size.

Maybe it makes more sense to start with these statistics to solve the problem. In other words, how can we start going back to eating pre-1980 portions of food.

There are many potential solutions including focusing on restaurant serving sizes, sugar substitutes, diabetes drugs that affect weight loss like Ozempic, Metformin that helps prevent diabetes for overweight people, or even more creative solutions such as adding an enzyme to reduce how much sugar gets absorbed into the bloodstream.

The point is, we need to solve the problem for everyone instead of focusing on disparities in outcomes that offer no clue to solving problems. Our individual choices affect our microbiome and our epigenetics which in turn affect disease.

As long as we have freedom of choice over what we eat, how much we exercise and a thousand other decisions, we should neither expect nor desire equality of behavioral driven health outcomes.

Unless, of course, we solve the problem—for everyone.